Part one of School of Engineering alumna Sangu Iyer’s exhaustive research on the events leading up to Jamshed Bharucha’s appointment as President.

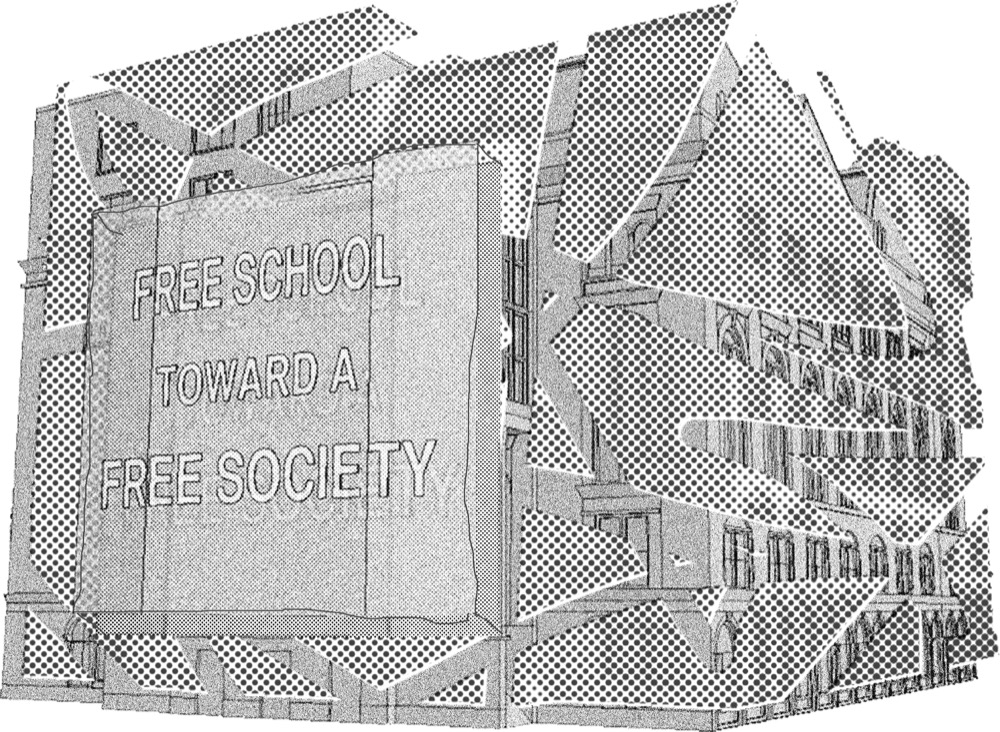

On November 17, 2011, at a student rally in Union Square organized by Occupy Wall Street, a young woman’s words echoed through the crowd via the people’s microphone: “Education should be as free as air and water.”

The rally came just a few weeks after Dr. Jamshed Bharucha, who became president of Cooper Union in July 2011, revealed the grim financial condition of the school and suggested that the historically tuition-free institution could no longer be free. “I’m not saying I want to charge tuition,” Bharucha said at a subsequent meeting in his office with alumni. “I’m saying the institution is going down. We have to have all options on the table and hopefully this is only the last resort.”

Cooper Union is currently only one of a handful of schools that offer tuition-free education to all enrolled students. Among them are Webb Institute in Long Island, Deep Springs College in California, and military academies such as West Point. Berea College in Kentucky accepts only low-income students, offering them tuition-free education in exchange for a labor requirement. Olin College, which was founded in 1997 as a free engineering school, switched from offering full tuition to half tuition after suffering endowment losses during the recession. But it wasn’t long ago that free education was within reach at some of the nation’s best public universities. The City University of New York, once called the Free Academy, only started charging tuition in the 1970s. Several decades ago, state residents could attend the University of California for free.

In an era in which air and water have become increasingly commoditized, education at Cooper Union until now has been spared the fate of the University of California. This small art, architecture, and engineering college, with a student body of fewer than one thousand students, is dealing not only with a financial crisis but also an existential one. What is playing out at this East Village institution speaks both to the national debate about debt, labor, and the affordability of higher education and to Cooper Union’s history, which in its early years was so closely tied to the desires of the nation.

For more than 150 years, Cooper Union has been a symbol of a certain American dream. Founder Peter Cooper himself seemed to come right out of one of Horatio Alger’s tales. Born during the Washington Administration, in 1791, he rose through a series of craftsman jobs, with almost no formal education, to acquire wealth through innovation. His inventions included the first gelatin dessert, the structural I-beam, and perhaps most notably, the first steam locomotive to be used on a common carrier railroad. Cooper also devoted decades to public service, becoming a New York City alderman, supporting the antislavery and Native American reform movements, and at 85 serving as the presidential nominee of the populist Greenback Party. He became one of the wealthiest men in New York, but unlike his robber-baron contemporaries, Cooper believed that wealth was a public trust.

Perhaps his greatest legacy and act of philanthropy was the founding of an educational institution for the working classes, free of charge, which since opening its doors in 1859 has professed not to discriminate by race, gender, class, or creed. The original charter called for free instruction at night in the sciences, a day school of design for “respectable” females, a free reading room, and free public lectures. When funds became available, a polytechnic school was to be created. Cooper also hoped to establish “The Associates of Cooper Union,” modeled after the Society of Arts in London. Its reach was to be vast and inclusive, including alumni, professional societies, members of the press, public school teachers, and other civil servants.

Cooper was influenced by the free École Polytechnique in Paris, which a friend had described to him. “What interested me most deeply was the fact that hundreds of young men were there from all parts of France, living on a bare crust of bread a day to get the benefits of those lectures.” That deep desire and want of education was something Cooper empathized with, having had no access to education as a young man. “It was this feeling which led me to provide an institution where a course of instruction would be open and free to all who felt a want of scientific knowledge, as applicable to any of the useful purposes of life,” Cooper said in his 1864 commencement address.

From the outset, Cooper Union opened its doors to debate. The basement of the Foundation Building housed the Great Hall auditorium, where Abraham Lincoln delivered his “Right Makes Might” speech challenging Stephen Douglas in 1860, and started out on the road to the White House. During the following years, The Great Hall provided a space for debating, rallying, and organizing the abolition, suffrage, labor, and Native American reform movements. Fredrick Douglass spoke there in 1863. Susan B. Anthony had an office at the school. PJ McGuire and Samuel Gompers met taking night classes at Cooper Union and went on to start the American Federation of Labor. Cooper welcomed Oglala Sioux Chief Red Cloud when Red Cloud addressed the Great Hall in 1870. The NAACP and the Red Cross were chartered and convened their first meetings at Cooper Union.

When the school opened, women could attend either the Female School of Art during the day or the coeducational Free Night School of Science. Women who attended night classes during Cooper Union’s first decades had backgrounds that ranged from wealthy to working class. The noted exception to Cooper Union’s policy of free instruction occurred was the School of Art, run by a Ladies Advisory Council who had overseen the New York School of Design before it was absorbed by Cooper Union. These “benevolent and enlightened ladies” pleaded with the Cooper trustees to make an allowance for some paying pupils, who would be called “amateur students.” According the school’s first annual report, the trustees “were at first opposed to this deviation” but agreed on the condition that the number of amateurs be limited so as not to exclude the industrial pupils. These amateurs paid between one and two dollars a week for instruction in drawing, pastel, watercolor, or oil painting until the 1880s, when they disappeared from mention in annual reports. Discussion of the amateur class was removed from Cooper Union’s bylaws during their next revision in 1911.

”The dealers in money have always been the dangerous class,” Cooper wrote in the last year of his life. “There may, at some future day, be a whirlwind precipitated upon the moneyed men of this country.” In his unpublished autobiography, Cooper recounts his frustrations with the bankers who controlled Congress and were creating a national debt. They had the power to control the volume of currency, issue credit, and charge unfairly high interest rates. In the spirit of Cooper’s beliefs, the original Cooper Union charter stated that the trustees should never mortgage the property or go into debt for more than $5,000 a year (except in anticipation of rents and revenues), and that they would be held personally liable for any deficit. In his turn-of-the century biography, Rossiter Raymond notes that Cooper claimed to pay all his debts every Saturday night, tracing “that horror of debt” to the time of debtors’ prisons.

How was Cooper’s vision sustained after his death? How did his school maintain its policy of free education? During its first four decades, Cooper Union was largely supported by Cooper and his family, and those years were not without struggle. To supplement gifts and donations, part of the Foundation Building was rented out to commercial tenants. Cooper and his son-in-law Abram Hewitt had asked Columbia University “with its large and growing revenues” and the Board of Education, which controlled the Free Academy, for support, but neither was willing to offer it.

In 1902 Andrew Carnegie, who had previously described himself as a “humble follower of Peter Cooper,” made a $600,000 gift to Cooper Union, one that was matched by Cooper’s heirs, who donated a property on Lexington Avenue. These gifts ensured Cooper Union’s endowment and allowed it to build the polytechnical school called for in the original charter and stop renting out part of the building to commercial tenants. The “Vanderbilt flats,” as the property was then called, now sits beneath the Chrysler Building. The school receives rent and the equivalent of property taxes from this piece of real estate, which in turn secured Cooper Union’s ability to provide full tuition scholarships.

Cooper Union was a lesson in humility, perseverance, and resourcefulness. One of the things I deeply valued about it was its diversity. Many of my classmates were immigrants or first-generation Americans like me. Cooper was a place where we could celebrate our own and one another’s cultures, and every year, we put on an annual culture show in the Great Hall.

During the decade after I left Cooper Union, as its operating expenses continued to rise, its future became increasingly uncertain. When George Campbell Jr., took over as president in 2000, he undertook a major development plan that was intended to increase revenue and modernize the campus. The proposal, which was approved by the Board of Trustees, was to demolish the engineering building at 51 Astor Place and replace it with a large commercial tower. The Hewitt Building, where art classes were held, would also be destroyed. It would be replaced with a taller structure with more modern facilities, where academic programs would be consolidated under one roof.

This “general, large-scale development” plan required approval from the Department of City Planning and was subject to a public review process. In an Environmental Impact Statement, the school claimed the new plan was necessary to “contend with two challenges: to continue funding the full-tuition scholarships for all students and generate the necessary resources to be a leader in its degree programs.” This argument didn’t persuade East Village residents, who loudly protested the proposed changes to their neighborhood, but in the end the city planning commission granted conditional approvals to Cooper Union. ANew York Times article in 2002 noted that “the commissioners said the public good that Cooper Union does by offering free education for its students—most of them New Yorkers—outweighed the impact on the community.”

Even after the land use was approved, the school had more hurdles to overcome. After it failed to meet its fundraising goals for the construction of the New Academic Building in 2006, Cooper Union submitted a petition to the New York State Supreme Court seeking permission “to use the Chrysler Building as security for the loan of up to $175 million,” releasing it from the restrictions of the 1902 deed. The school argued to the Supreme Court, as it had to the City Planning Commission, that the development plan was essential to maintain the school’s standing and financial well-being as a tuition-free institution.

The plans for the new building divided the Cooper community. Faculty members questioned the need for building and pleaded that the school make do with existing spaces. One letter from an engineering professor to President Campbell in 2006 noted the “great deal of discontent amongst the engineering faculty. At a faculty meeting on 5/18 the engineering faculty roundly rejected the new building by a vote of 16–6 in a closed ballot.”

Nevertheless, the New York Supreme Court granted Cooper Union’s request and construction began. A 2009 Wall Street Journal article lauded Cooper Union for being able to build its green LEED Platinum certified New Academic Building on 41 Cooper Square while other colleges were being forced by the economic crisis to halt their campus expansions. Newspapers reporting on Campbell’s retirement in 2011 noted that he grew the endowment, balanced the budget, and brought fiscal stability to the college.

So it came as huge shock to alumni and students when Bharucha announced in October 2011 that with an annual deficit of $16 million and an unrestricted endowment of $45 million, the school’s available funds were on the verge of depletion. Just a few weeks before, St. Mark’s Bookshop had announced that Cooper Union was raising its rent and launched a massively popular petition to save the store, which led to Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer negotiating a rent reduction. There was no mention of the fact that Cooper Union itself was in crisis.

What had happened? It appeared that Cooper Union’s investment portfolio had not been immune to the crash of the financial markets. As the trustees subsequently explained, “projections made in 2008 conservatively anticipated a 2009 return of $6 million but instead our portfolio suffered a loss in that year of $22 million.” Meanwhile, the goal to reduce operating expenses by 10 percent by 2011 had never been achieved, and the college was paying $10 million a year of the $175 million loan taken out from Metropolitan Life. One can only imagine what Peter Cooper would think of the debt the school currently holds.

The plan proposed by President Campbell was supposed to ensure Cooper Union’s ability to grant full scholarships, and was approved based on Cooper Union’s reputation as a provider of free education. Ten years later, that plan appears to have jeopardized the full scholarship policy it was put in place to secure. (The board of trustees has argued otherwise: “It is also important to state that 41 Cooper Square was not the cause of the current financial dilemma. Its construction relieved Cooper Union of the costs that would have had to be incurred to renovate the old engineering building and the Hewitt Building to make them acceptable sites for a 21st-century education and meet accreditation standards.”)

If tuition is implemented, some fear that the Chrysler Building’s tax equivalency payments to the school might face a serious challenge. There have been several legal cases questioning a private college’s receipt of property taxes, but the courts have consistently sided with Cooper Union and its service to the public good. By seeking new revenues from tuition, the school could threaten its largest and only reliable source of funding.

In the past, financial problems were solved by selling off assets, but Bharucha said there are no more assets to sell, and he is reluctant to shut programs down.

Bharucha said he hopes to have a sustainable financial model in place by 2018, the year the principal payment on the loan will kick in. But 2018 will also bring some relief. The legal document that negotiated the mortgage on the lease of the Chrysler Building states that the lease payments will increase to $32.5 million in 2018, $41 million in 2028, and $55 million in 2031. Bharucha argues that 2018 won’t bring enough relief to cover the rising cost of education. In the nearer term, Cooper Union could deplete its available funds by 2015.

I asked President Bharucha to what extent the tuition model has been developed. “On the question of how much tuition would be charged, how many would have to pay, and how much of it they would have to pay, we’ve hired a consultant,” Bharucha told me. “It’s a specialty now. It’s called enrollment management. We’ve hired one of the top enrollment management firms. They will do the market research.”

While Bharucha is not responsible for the financial woes he inherited, he is the creator of a new narrative for the school, one that supports a tuition-based model. In speeches and meetings over the past year, Bharucha has spoken about “reinventing” Cooper Union. A crucial part of this reinvention is replacing the founding principle of free education with a new commitment to “accessible” education. “Access,” Bharucha has said, means “enabling students of merit to benefit from a fine education that would otherwise be out of reach. We must always have this as a priority, regardless of how we solve our financial challenges.” References to tuition-free education are slowly being edited out of the administration’s language; when free education is mentioned, it is described as a “cherished aspect” rather than a core value of the school.

As students looked to Peter Cooper’s words to support their case against tuition, President Bharucha—in speeches, radio interviews, and meetings with alumni and stakeholders—invoked Cooper to support another argument. Bharucha took these opportunities to bring up the small fraction of “amateur” students at the women’s school of design who paid for their classes. In a speech in the fall of 2011, he stated, “It is important to note that in the early years, approximately the first forty years, tuition was charged at Cooper Union. It wasn’t until 1902, when Andrew Carnegie made a large gift to the institution, that a tuition-free education was granted to students.”

Bharucha looks to the amateurs as a sort of precedent, a justification for a tuition model. But the context and duration of the amateur program are misrepresented in Bharucha’s narrative. Paying students did not attend the school for the four decades, as Bharucha has repeatedly said; their presence can only be traced until the late 1880s. And the amateur program was not the norm at the school. It was clearly noted as an exception from the rule that instruction be “entirely gratuitous.” Attendance wasn’t mandatory for the amateur students, and they weren’t held to the same standards as the industrial pupils, who attended for free. The contemporary equivalent of an amateur class would not be a tuition-based model for undergraduate education, with some students funding the education of others, as Bharucha suggests. Instead the amateur class most resembles Cooper Union’s current fee-based continuing education programs (which themselves may be viewed as a deviation from the original mandate to provide free night instruction).

“There is a very fundamental framing conflict between the internal narrative of the institution and where the country is, for wanting those with means to contribute more so that others can have opportunity,” Bharucha said. He has often appropriated the language of the Occupy movement to suggest that Cooper students, who largely come from working and middle-class backgrounds, are the 1 percent. The administration has argued that charging some students to fund others would somehow level the field. Others argue that Cooper’s meritocracy is what ensures equal ground. They fear that if tuition is implemented, and the school is reliant on a certain amount of revenue from tuition, it will then become dependent on a certain percentage of its students being able to pay.

At a community forum in December 2011, Sam Messer, an assistant dean at the Yale School of Art and a Cooper alumnus, said, “There’s a lot of talk about the idea of tuition, and if you just say it as a sound bite it does seem fair: that the rich should pay their way.” But “what happens if you don’t have qualified students at that level? Then you have, in a sense, amateurs,” meaning that admissions to the school at large would no longer be entirely merit-based.

Beginning in December 2011, the newly formed grassroots coalition Friends of Cooper Union (FOCU), composed of alumni, students, faculty, and staff, met to generate its own solutions to Cooper’s crisis. The result was a document, “The Way Forward,” released in April 2012, that imagined a future without tuition and demanded more transparency and community engagement from the administration.

In late April 2012, coinciding with the publication of “The Way Forward,” I participated in a community summit organized by FOCU. Litia Perta, an adjunct professor who has taught on and off at Cooper Union since 2006, opened up the discussion by saying that she’s currently on unemployment and collects more money—“kind of by a lot”—than she has as an adjunct, and that while on unemployment she had the additional benefit of being able to defer her own student loan payments. “I could not afford to teach here this semester,” she said. “I think that seems really relevant.”

Perta made this statement on the same stage that launched the modern American labor movement. She also noted that about 70 percent of classes at Cooper Union are taught by adjuncts with no job security, health insurance, or other benefits. Nationally, about 75 percent of college classes are taught by adjuncts in similar situations today. Cooper was founded to educate the working classes, and now highly educated faculty members are among its working class.

Richard Stock, professor of chemical engineering and head of the faculty labor union, noted at a FOCU summit in December 2011 that operating expenses more than doubled between 1995 and 2010, going from $28 million to $68 million. Stock said that a large part of that increase could be attributed to growth and salary increases among nonacademic staff. In fact then-president George Campbell, Jr. was ranked by the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2009 among the ten highest-paid college presidents, with an annual compensation package valued at $688,773, for overseeing a school with fewer than 1,000 students. According to tax records the ten highest-paid officers at Cooper collectively made approximately $2.9 million in 2010. Meanwhile the approximately fifty-six full-time faculty members made roughly $5 million combined.

T. C. Wescott, the vice-president of finances of the college, has noted that a recent $4 million in cuts were largely directed at the administration, and that in 2013 the overall budget is approximately half administrative, half academic, in line with other institutions. But it should be asked whether this is necessary for a school with a very small student body and a full-scholarship policy. “The Way Forward” contains a modest proposal that the top three administrative officers defer a third of their compensation until 2018, when the college will receive increased income from the Chrysler Building. Bharucha, whose compensation package has been valued at about $750,000, has pledged to donate 5 percent of his base salary to the school.

Underpaid faculty, overpaid administrators, and campus expansions that drive up the cost of education can be found at colleges large and small across the country. At the April 2012 community summit, art student Alan Lundgard noted that should the tuition model go through, “Our problems will exemplify our country’s inability to provide for its citizens an education unencumbered by the barriers of class privilege or wealth. We must make it clear, that it is not the unique ideals of this institution that are built to fail, but the educational disasters that run rampant everywhere else in this country.”

In August 2012, Bharucha charged the deans and faculty of each school with coming up with academic programs that would meet prescribed revenue targets ($6 million, $3.6 million, and $2.4 million for the engineering, art, and architecture schools, respectively). If faculty did not meet these revenue targets, they would be threatened with the closure of their school.

On December 3, 2012, eleven Cooper Union art students barricaded themselves on the top floor of the Foundation Building and draped across it a red banner that read “Free Education to All.” These students had three demands: that the administration publicly affirm its commitment to free education; that the board immediately implement more transparent and democratic decision-making structures; and that Bharucha step down. The first day of the occupation coincided with a day of action at Cooper Union organized in collaboration with Occupy Wall Street, All in the Red, and Strike Debt. Several faculty members joined the student occupiers at a joint press conference. That evening, speakers from other schools rallied in solidarity with students of Cooper Union.

Although their demands had not been met, the students left the building after one week to plan their next action. The faculty did as they were told and came up with various revenue-based programs, even as they continued to express their opposition to a tuition model. In December 2012, the art school faculty refused to vote on the new programs they had proposed. This February, the art faculty issued another statement, “reaffirming our belief that The Cooper Union is not only the last citadel of the social reforms movement of the 19th century, but is in fact the vanguard of the 21st century—a beacon of access to free education.” In response, the administration refused to admit early decision students to the art school. Faced with the real possibility of their school closing, the art faculty gave in and submitted their proposals for revenue-based graduate, continuing education, and high-school summer courses.

The administration now seems close to announcing a decision regarding tuition. On March 1, at the request of the alumni association, trustees appeared again at the Great Hall to answer questions from the community. Trustee Thomas Driscoll said at the forum that he didn’t think the school could shrink to sustainability—crucially, he was referring to shrinking academic programs and not administrative costs. Faculty, students, and alumni asked whether Cooper could live within its revenue stream from the Chrysler Building, $40 million a year, cut administrative costs, and grow its endowment through more effective, alumni-led fundraising.

One recommendation made by “The Way Forward” is that Cooper Union “grow down.” Rather than invest in fee-based programming, what if Cooper instead focused on strengthening its roots and giving back to the community, spreading the culture of free education and illustrating that Cooper’s benefits are not just for the few who merit entry? There are existing programs in which Cooper Union students tutor and mentor New York City public school students. Some of these are facing budget cuts. Rather than curb these efforts, what if Cooper Union grew them? “If you can do that, your community will fight for you,” Perta said. She later posted on the Save Cooper Union Facebook page a line from a wild fermentation cookbook: “To be indispensable to the organisms with which one shares an environment—that is the strategy that ensures successful . . . and continued survival.” This would represent another kind of union with the community, in which education would be considered as vital as air and water.

←

Previous Chapter:

Two Educations for the Price of None

An open letter to incoming freshmen about self-care and Cooper politics from School of Art transfer student Jakob Biernat.